|

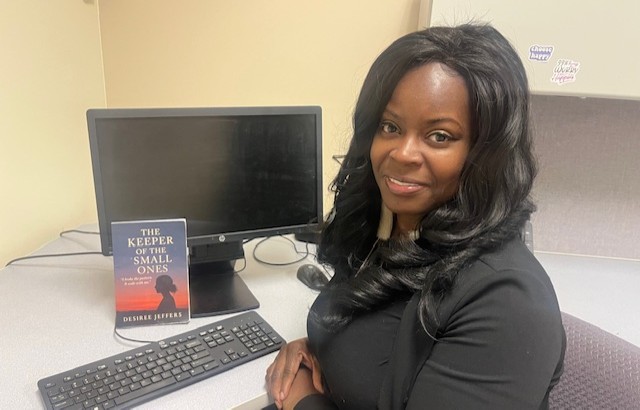

Hidden Heroes: Desi Jeffers

|

|

Hidden Heroes is a new Do Right By Kids series highlighting the people who work the front lines in the child welfare system. These individuals who choose to serve their communities share a common pull—they are drawn to helping others.

One such person is CPS caseworker Desi Jeffers. Her story is unique, as she has experienced the system from the inside, as a foster care child. She published a book last year about her life experiences, which ultimately led her to her current profession.

|

|

|

|

|

“Prior to joining CPS, I worked in the psych ward at Strong Hospital,” said Jeffers. “I was responsible for making sure patients didn’t hurt themselves.” She thought about becoming a police officer—whose role is to protect and serve—as she grew up protecting her two siblings in a household rife with abuse and neglect.

“I like helping people, so I applied to be a CPS caseworker,” she said. “I have no problem speaking up, so I can be a voice for these kids.”

Jeffers, who was adopted by her foster care parents, learned to speak up at an early age. Last year, she took an Ancestry test to learn more about her biological father, whom she had never met. The results led her to a newspaper article where she read about the day she and her siblings were removed from their home.

“I remember my childhood, but there were chunks missing,” she said. She wasn’t prepared for the horrific scene described in the article. But what struck her most was the description of her, as recounted by the police captain involved in the case: “She made it very clear that the children did not want to go back to that house.” At only five years old, her voice was heard.

In contrast to Jeffers’ personal story, which the article described as “one of the worst” cases, removing children and placing them in foster care is typically the last resort in cases of abuse or neglect.

“One of the biggest misconceptions is that we want to break up families,” said Jeffers. “CPS is going to intervene if you don’t do right by kids, but ideally, we make a plan with families to give them power.”

|

|

|

|

“I’ve been with CPS investigations for 10 years,” said Jeffers. “When a report of suspected child abuse or neglect is received, I’m the one who goes to the house to meet with kids and families.”

As the first person to interview kids in an investigation, Jeffers leverages her own past trauma to connect and empathize with them.

“I’m able to really put myself in their shoes and feel what those kids are feeling,” she said. “The hardest part of my job is that I have to see kids who are hurt—bruises, broken limbs—and sometimes listen to sex abuse stories. But being the person they talk to feels like a win to me. I love that part of my job.”

Jeffers said there is no “typical” day, that every day in her role is different. When she’s on rotation and gets a case, she will review it with her supervisor, noting any family history with CPS, before heading out to interview the child(ren).

“We recently had a case of domestic violence that involved a mom and her baby,” said Jeffers. “We were able to get them into a shelter together, even though all the shelters were full, which took some time to coordinate.”

She handles 2-3 cases per week, with a caseload at any given time of 15-20 open cases. Every interaction must be documented, so she considers having her case notes up to date a small win in her daily routine.

“Our number one goal is to keep families together,” she stressed. “In my role, success is when we can advocate for a child or family to make sure they have what they need to be successful.”

|

|

|

|

In her decade on the job, Jeffers has seen all kinds of families with different challenges. She makes the distinction between malicious neglect vs. being a victim of circumstances.

“We see lots of generational trauma and poverty in our cases,” she said. “Just because families are poor doesn’t mean they don’t love their kids.”

Jeffers urges mandated reporters to differentiate between poverty and neglect.

“Consider when it could be more appropriate to tap into resources instead of calling CPS,” she said. “I never want to discourage anyone from calling CPS, but make sure what you’re seeing is not a problem that resources could help. You will be appreciated for looking out for the safety and welfare of the children.”

Even though she’s seen it all—and personally experienced the worst—Jeffers keeps going because the kids need her.

“All the little faces that I get to see, even infants,” she said, “the potential help and influence I can give, to be someone’s guardian angel—that’s what keeps me going.”

Her advice for anyone thinking about a career with CPS is to follow your heart and give it a try. She said it’s not for everyone, but people’s lives depend on it. It’s an opportunity to change the trajectory of someone’s life.

“All caseworkers bring something unique to the job,” she said. “Everyone grows into the role to become the best role model they can be. I still remember my caseworker’s name.”

|

|

|

|

RESOURCES:

“The Keeper of the Small Ones”

by Desiree Jeffers

https://a.co/d/fAl4Igx

Is there a topic related to child protection that you would like the Do Right By Kids newsletter to explore?

Tell Us About It!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|